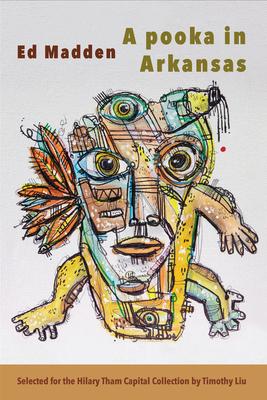

Poetry. Selected by Timothy Liu for the Hilary Tham Capital Collection. Madden's mastery of the American lyric combines intellect, heart, and courage as he explores growing up queer in the rural fundamentalist South. The poems anatomize a society of shaming and shunning under the guise of love, fighting free to the theme of finding where we belong. The poems work deep into the linguistic textures of his subjects, from queer love to the loss of a parent. The figure of the pooka (or puca) haunts the pages, embodying both good and bad luck, sorrow and hope.

Says Timothy Liu: "This book redeems the curse of where and what we are born into by conjuring spells. Bestial. Animistic. The poet retroactively strutting around his flanks like a mythic centaur, or if you like, a domestic ass. This book flies in the face of making the rough places plain and the crooked straight. You won't have to have grown up queer in the deep rural South to be touched by the lyrical antics that go on here, this alternative gospel spreading its haunches in the hay till every knee bow, every tongue confess, this chorus of Hallelujah inflected/infected by its own down and dirty twang."

Nathalie Anderson adds: "Pooka, wolf, coyote: what if we're the monster our parents warn us against? Ed Madden's poems about growing up queer in the rural fundamentalist South anatomize a society of shaming and shunning under the guise of love - the mother who 'grinds her children, ' 'crushes them'; the father with 'his head encased by a tiny church - as if the church were a vise, a mask, a hood.' Drawing on Irish folklore, on fairy tales, on Bible stories, Madden evokes an inner landscape at once real and surreal, at once loving and diminishing. His poems indict that community - 'you did not remember what big teeth they had, / what claws' - and gesture also toward the fascination of the forbidden - 'What he wore that day was darkness, / a silver shimmer of teeth.' Within this closed rural world, heteronormity sours into self-disgust, and desire terrifies: 'some of us were made to be ridden, riddled, riven.' Yet in tracing the 'practices' of a certain sort of situated fundamentalism, Madden refuses its dread and so redefines and recuperates the supposedly 'monstrous': 'I am not / handsome. I am not wholesome. I am not holy. I am not coming home.' These poems shine, they bite, they bristle and ripple and chuckle and spur. They turn shame aside to offer instead 'the man I will meet, ' 'the brush of his mouth, ' 'the hot water bottle of him.' Oh yes, they satisfy."