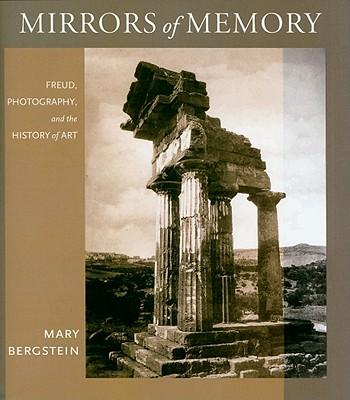

Photographs shaped the view of the world in turn-of-the-century Central Europe, bringing images of everything from natural and cultural history to masterpieces of Greek sculpture into homes and offices. Sigmund Freud's library--no exception to this trend--was filled with individual photographs and images in books. According to Mary Bergstein, these photographs also profoundly shaped Freud's thinking in ways that were no less important because they may have been involuntary and unconscious.In Mirrors of Memory, lavishly illustrated with reproductions of the photos from Freud's voluminous collection, she argues that studying the man and his photographs uncovers a key to the origins of psychoanalysis. In Freud's era, photographs were viewed as transparent windows revealing objective truth but at the same time were highly subjective, resembling a kind of dream-memory. Thus, a photo of a ruined temple both depicted the particular place and conveyed a sense of loss, oblivion, of time passing and past, and provided entry into the language of the psychoanalytic project.Bergstein seeks to understand how various kinds of photographs--of sculptures; archaeological sites in Greece, Rome, and Egypt; medical conditions; ethnographic scenes--fed into Freud's thinking as he elaborated the concepts of psychoanalysis. The result is a book that makes a significant contribution to our understanding of early twentieth century visual culture even as it shows that photography shaped the ways in which the great archaeologist of the human mind saw and thought about the world.

Mirrors of Memory: Freud, Photography, and the History of Art

Photographs shaped the view of the world in turn-of-the-century Central Europe, bringing images of everything from natural and cultural history to masterpieces of Greek sculpture into homes and offices. Sigmund Freud's library--no exception to this trend--was filled with individual photographs and images in books. According to Mary Bergstein, these photographs also profoundly shaped Freud's thinking in ways that were no less important because they may have been involuntary and unconscious.In Mirrors of Memory, lavishly illustrated with reproductions of the photos from Freud's voluminous collection, she argues that studying the man and his photographs uncovers a key to the origins of psychoanalysis. In Freud's era, photographs were viewed as transparent windows revealing objective truth but at the same time were highly subjective, resembling a kind of dream-memory. Thus, a photo of a ruined temple both depicted the particular place and conveyed a sense of loss, oblivion, of time passing and past, and provided entry into the language of the psychoanalytic project.Bergstein seeks to understand how various kinds of photographs--of sculptures; archaeological sites in Greece, Rome, and Egypt; medical conditions; ethnographic scenes--fed into Freud's thinking as he elaborated the concepts of psychoanalysis. The result is a book that makes a significant contribution to our understanding of early twentieth century visual culture even as it shows that photography shaped the ways in which the great archaeologist of the human mind saw and thought about the world.