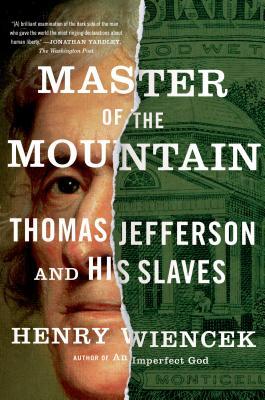

Henry Wiencek's eloquent, persuasive Master of the Mountain--based on new information coming from archival research, archaeological work at Monticello, and hitherto overlooked or disregarded evidence in Thomas Jefferson's own papers--opens up a huge, poorly understood dimension of Jefferson's faraway world. We must, Wiencek suggests, follow the money.

Wiencek's Jefferson is a man of business and public affairs who makes a success of his debt-ridden plantation thanks to what he calls the "silent profit" gained from his slaves--and thanks to the skewed morals of the political and social world that he and thousands of others readily inhabited. It is not a pretty story. Slave boys are whipped to make them work in the nail factory at Monticello that pays Jefferson's grocery bills. Slaves are bought, sold, given as gifts, and used as collateral for the loan that pays for Monticello's construction--while Jefferson composes theories that obscure the dynamics of what he himself called "the execrable commerce." Many people saw a catastrophe coming and tried to stop it, but not Jefferson. The pursuit of happiness had become deeply corrupted, and an oligarchy was getting very rich. Is this the quintessential American story?

Henry Wiencek's eloquent, persuasive Master of the Mountain--based on new information coming from archival research, archaeological work at Monticello, and hitherto overlooked or disregarded evidence in Thomas Jefferson's own papers--opens up a huge, poorly understood dimension of Jefferson's faraway world. We must, Wiencek suggests, follow the money.

Wiencek's Jefferson is a man of business and public affairs who makes a success of his debt-ridden plantation thanks to what he calls the "silent profit" gained from his slaves--and thanks to the skewed morals of the political and social world that he and thousands of others readily inhabited. It is not a pretty story. Slave boys are whipped to make them work in the nail factory at Monticello that pays Jefferson's grocery bills. Slaves are bought, sold, given as gifts, and used as collateral for the loan that pays for Monticello's construction--while Jefferson composes theories that obscure the dynamics of what he himself called "the execrable commerce." Many people saw a catastrophe coming and tried to stop it, but not Jefferson. The pursuit of happiness had become deeply corrupted, and an oligarchy was getting very rich. Is this the quintessential American story?Paperback

$21.00