The network of freemasons and Masonic lodges in the Middle East is an opaque and mysterious one, and is all too often seen - within the area - as a vanguard for Western purposes of regional domination. But here, Dorothe Sommer explains how freemasonry in Greater Syria at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century actually developed a life of its own, promoting local and regional identities, and crucially distancing itself from the possibilities of Western interference. She stresses that during the rule of the Ottoman Empire, freemasonry was actually one of the first institutions in what is now Syria and Lebanon which overcame religious and sectarian divisions. Indeed, the lodges attracted more participants - such as the members of the Trad and Yaziji Family, Khaireddeen Abdulwahab, Hassan Bayhum, Alexander Barroudi and Jurji Yanni - than any other society or fraternity.

Focusing on Tripoli, Beirut and Mount Lebanon, Sommer explores the function of the Masonic lodges as a social institution, and examines the ways in which ideas of tolerance, solidarity and fraternity were conceived of and developed. She finds that far from being predominately characterised by a detachment from the local surroundings, the Masonic lodges were often attempting to adapt the ideological framework of freemasonry to suit the Ottoman community, whilst still being part of a wider Masonic culture. Unlike lodges in Egypt working under the United Grand Lodge of England, foreigners were almost not represented amongst the lodges in Ottoman Syria, which made these Syrian lodges more attuned to local sensibilities. Freemasonry in the Ottoman Empire analyses the social and cultural structures of the Masonic network of lodges and their interconnections at a pivotal juncture in the history of the Ottoman Empire, making it invaluable for researchers of the history of the Middle East.

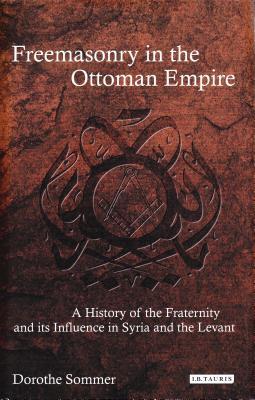

Freemasonry in the Ottoman Empire: A History of the Fraternity and Its Influence in Syria and the Levant

The network of freemasons and Masonic lodges in the Middle East is an opaque and mysterious one, and is all too often seen - within the area - as a vanguard for Western purposes of regional domination. But here, Dorothe Sommer explains how freemasonry in Greater Syria at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century actually developed a life of its own, promoting local and regional identities, and crucially distancing itself from the possibilities of Western interference. She stresses that during the rule of the Ottoman Empire, freemasonry was actually one of the first institutions in what is now Syria and Lebanon which overcame religious and sectarian divisions. Indeed, the lodges attracted more participants - such as the members of the Trad and Yaziji Family, Khaireddeen Abdulwahab, Hassan Bayhum, Alexander Barroudi and Jurji Yanni - than any other society or fraternity.

Focusing on Tripoli, Beirut and Mount Lebanon, Sommer explores the function of the Masonic lodges as a social institution, and examines the ways in which ideas of tolerance, solidarity and fraternity were conceived of and developed. She finds that far from being predominately characterised by a detachment from the local surroundings, the Masonic lodges were often attempting to adapt the ideological framework of freemasonry to suit the Ottoman community, whilst still being part of a wider Masonic culture. Unlike lodges in Egypt working under the United Grand Lodge of England, foreigners were almost not represented amongst the lodges in Ottoman Syria, which made these Syrian lodges more attuned to local sensibilities. Freemasonry in the Ottoman Empire analyses the social and cultural structures of the Masonic network of lodges and their interconnections at a pivotal juncture in the history of the Ottoman Empire, making it invaluable for researchers of the history of the Middle East.