These are stories from far off places, in far off and very different times, stories of everyday people doing everyday things. With his brilliant memory and attention to detail, Rafal Feliks Buszejkin explained what he and the other children did in Russia in the 1910s to entertain themselves in the winter. He never attended cheder, but with a tutor, he memorized his speech for his Bar Mitzvah at the Great Synagogue of Warsaw. In high school there was that band of youths who played poker and got into mischief. He was one of them. He boxed, he worked out and built his muscles, he did track and field, raced bicycles. He failed his last year of high school. He was not a typical Eastern European Jew of that time.

He told stories of wolves in the forest in 1917, and bankruptcy at home in 1933. Stories of university days in France and months spent with Sephardic Jews in a small desert town in Algeria where he set up a Maccabi sports club.

There are love stories, stories of rich men who lose it all and poor ones who become rich. Because he had studied agronomy, he was employed all through the war and all through his life. His war-time stories from Siberia tell of hard work, trying to have enough to eat, and avoiding the NKVD. Kazakh stories tell of a culture that was a mix of western and eastern and of spending two months in a Soviet prison. Postwar brought him from the steppes of Kazakhstan to the French Riviera, then to the Dominican Republic where he farmed in a collective Jewish refugee settlement. And finally, the United States, where there were jobs, the possibility of making a good life, and no secret police.

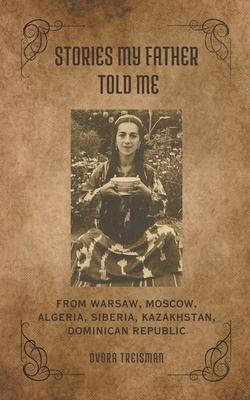

Dvora Treisman wrote this book based on a memoir her father wrote and stories she had heard at the dining room table all her life, and she has kept it as true to his telling as possible.