Book

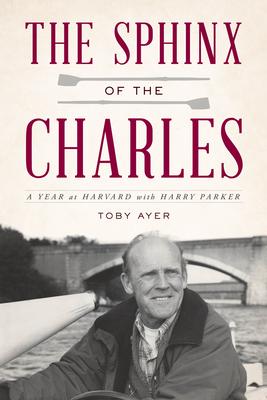

The Sphinx of the Charles: A Year at Harvard with Harry Parker

by Toby Ayer

(Write a Review)

Paperback

$19.95

Though a fundamentally compelling figure, Parker's famous reticence means that few managed to spend much time close to him. Since he made no attempt to explain himself, legends abound: he never got older; he could control the weather; he could walk on water. The Sphinx of the Charles: A Year at Harvard with Harry Parker takes the reader not only inside the Harvard boathouse, but into the coaching launch with Parker. We see how he coached--how many words he actually uttered--as he guided his team through a year of training, and hear about his life in the sport. We see a paradox: Parker remained remarkably constant over the last forty-five years, yet he constantly evolved, changed his style, and used every means at his disposal to build champion crews. The Sphinx of the Charles goes inside the rowing world in a way hasn't been done before, putting the reader in the passenger seat next to one of the most successful coaches of all time. Parker is a historical icon, part of a tradition that goes back to the beginning of intercollegiate athletics in America. His story needs to be told.

The Sphinx of the Charles is fundamentally a chronicle of a year with the Harvard team and a profile of Harry Parker as he was, five years before his death: comfortable in his position as elder and master of the sport, reflective but not nostalgic, aged but nearly impervious to aging. It is driven by Ayer's own observations of Parker from his seven years of coaching and training at the Harvard boathouse, but especially from one academic year, 2008-9. he shadowed him for a few days every week from September to June, observing practices both on and off the water, and interacting with the team. The present tense of the narrative reflects this immediacy, but also the sense that Parker has endured and continues to endure. And though The Sphinx of the Charles is not a biography in the usual sense, Parker's life and career were rich and extraordinary and they must be explored.

Thus, each chapter carries the reader another month through the training year at Harvard, with vivid descriptions of team practices and a sense of progress towards the spring racing goals. From the passenger seat next to Parker we watch the rowers tackling the daily workouts, honing their mental and physical stamina along with their bladework, always trying to beat their teammates in the crew next to them, under Parker's watchful eye and ever-present megaphone. Parker makes asides in the launch that the rowers will never hear: remarks about the crews and their progress, passing wildlife, memories of his life in rowing, the river and its history, the sunlight on the water. Intertwined with the narrative are historical perspective, descriptions of the boathouse and the river, profiles of other coaches at Harvard, and impressions from rowers and coaches who worked with Parker over the previous forty-five years. Newspaper and magazine articles reveal how Parker was depicted, and how he revealed himself, to the rowing world and the public. The reader sees how Parker evolved and yet remained consistent. Parker was responsible for turning college crew into a three-season sport: varsity rowers now practice every day from September to early June. There are long "head" races in the fall, including the famous Head of the Charles in Boston. The winter months are a period of tough training on rowing machines and indoor "tanks," lasting until the ice breaks up on the river. The official season of "sprint" races doesn't start until April, and includes two championship regattas, the Harvard-Yale Race, and (if they win one of the championships) the Henley Royal Regatta in England.

Though a fundamentally compelling figure, Parker's famous reticence means that few managed to spend much time close to him. Since he made no attempt to explain himself, legends abound: he never got older; he could control the weather; he could walk on water. The Sphinx of the Charles: A Year at Harvard with Harry Parker takes the reader not only inside the Harvard boathouse, but into the coaching launch with Parker. We see how he coached--how many words he actually uttered--as he guided his team through a year of training, and hear about his life in the sport. We see a paradox: Parker remained remarkably constant over the last forty-five years, yet he constantly evolved, changed his style, and used every means at his disposal to build champion crews. The Sphinx of the Charles goes inside the rowing world in a way hasn't been done before, putting the reader in the passenger seat next to one of the most successful coaches of all time. Parker is a historical icon, part of a tradition that goes back to the beginning of intercollegiate athletics in America. His story needs to be told.

The Sphinx of the Charles is fundamentally a chronicle of a year with the Harvard team and a profile of Harry Parker as he was, five years before his death: comfortable in his position as elder and master of the sport, reflective but not nostalgic, aged but nearly impervious to aging. It is driven by Ayer's own observations of Parker from his seven years of coaching and training at the Harvard boathouse, but especially from one academic year, 2008-9. he shadowed him for a few days every week from September to June, observing practices both on and off the water, and interacting with the team. The present tense of the narrative reflects this immediacy, but also the sense that Parker has endured and continues to endure. And though The Sphinx of the Charles is not a biography in the usual sense, Parker's life and career were rich and extraordinary and they must be explored.

Thus, each chapter carries the reader another month through the training year at Harvard, with vivid descriptions of team practices and a sense of progress towards the spring racing goals. From the passenger seat next to Parker we watch the rowers tackling the daily workouts, honing their mental and physical stamina along with their bladework, always trying to beat their teammates in the crew next to them, under Parker's watchful eye and ever-present megaphone. Parker makes asides in the launch that the rowers will never hear: remarks about the crews and their progress, passing wildlife, memories of his life in rowing, the river and its history, the sunlight on the water. Intertwined with the narrative are historical perspective, descriptions of the boathouse and the river, profiles of other coaches at Harvard, and impressions from rowers and coaches who worked with Parker over the previous forty-five years. Newspaper and magazine articles reveal how Parker was depicted, and how he revealed himself, to the rowing world and the public. The reader sees how Parker evolved and yet remained consistent. Parker was responsible for turning college crew into a three-season sport: varsity rowers now practice every day from September to early June. There are long "head" races in the fall, including the famous Head of the Charles in Boston. The winter months are a period of tough training on rowing machines and indoor "tanks," lasting until the ice breaks up on the river. The official season of "sprint" races doesn't start until April, and includes two championship regattas, the Harvard-Yale Race, and (if they win one of the championships) the Henley Royal Regatta in England.

Paperback

$19.95