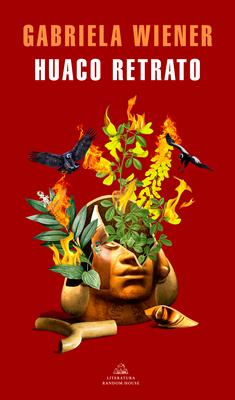

A huaco portrait is a pre-Hispanic ceramic piece that sought to represent indigenous faces with the greatest possible precision. It is said that it captured the soul of the person, a record that has survived hidden in the broken mirror of the centuries. We are in 1878, and the Jewish-Austrian explorer Charles Wiener is preparing to be recognized by the academic community at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, a great fair of "technological progress" that has among its attractions a human zoo, the culmination of scientific racism and the European imperialist project. Wiener has been close to discovering Machu Picchu, he has written a book about Peru, he has taken close to four thousand huacos and also a child. One hundred and fifty years later, the protagonist of this story walks through the museum that houses the Wiener collection to recognize herself in the faces of the huacos that her great-great-grandfather plundered. With no more baggage than her loss or any map other than that of her open wounds, the intimate and the historical ones, she pursues the traces of the family patriarch and those of the bastardy of his own lineage -which is that of many-, the search for identity in our time: an archipelago of abandonment, jealousy, guilt, racism, ghostly vestiges hidden in families and the deconstruction of a desire stubbornly anchored in a colonial thought. There is trembling and resistance in these pages written with the breath of someone who picks up the pieces of something that was broken long ago, hoping that everything will fit together again.

A huaco portrait is a pre-Hispanic ceramic piece that sought to represent indigenous faces with the greatest possible precision. It is said that it captured the soul of the person, a record that has survived hidden in the broken mirror of the centuries. We are in 1878, and the Jewish-Austrian explorer Charles Wiener is preparing to be recognized by the academic community at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, a great fair of "technological progress" that has among its attractions a human zoo, the culmination of scientific racism and the European imperialist project. Wiener has been close to discovering Machu Picchu, he has written a book about Peru, he has taken close to four thousand huacos and also a child. One hundred and fifty years later, the protagonist of this story walks through the museum that houses the Wiener collection to recognize herself in the faces of the huacos that her great-great-grandfather plundered. With no more baggage than her loss or any map other than that of her open wounds, the intimate and the historical ones, she pursues the traces of the family patriarch and those of the bastardy of his own lineage -which is that of many-, the search for identity in our time: an archipelago of abandonment, jealousy, guilt, racism, ghostly vestiges hidden in families and the deconstruction of a desire stubbornly anchored in a colonial thought. There is trembling and resistance in these pages written with the breath of someone who picks up the pieces of something that was broken long ago, hoping that everything will fit together again.

Paperback

$18.95