In November 1664, rumours began winding their way through crowded, filthy, stinking alleyways about the death of two Frenchmen from the Plague at Long Acre. The plague had raged in Amsterdam with incredible violence the year before, as some still remembered, and it appeared to have its made to London by boat. At first, the family with whom the Frenchmen were staying, and then those who had caught the invisible contagion, attempted to conceal it, but soon enough the deaths began to mount, and the cat was out of the bag. Along with the disgusting buboes, the dead carts, and the secret mass graves, people's fervid imagination snowballed too, conjuring all manner of horrors-about the symptoms, about the disease, about pestilential houses filled with rotting corpses-sweeping the city with a foul wave of paranoia and terror. Who had it? Was it in the air? Was it divine punishment? Whither could one flee? Defoe, who lived through these events during infancy, and apparently basing his narrative on his uncle's diary, plus a variety documents, tells the story in the manner of a witness account. Its frightening immediacy makes it far superior, and vastly more engrossing, than Hodges' formal, medically-focused volume on the same subject. In the end, the plague claimed over 68,000 lives, about a quarter of the city's population. Sociologically and in terms of the official response, astonishing, sometimes tragicomical parallels, emerge in the mind of the modern reader, between what became known as the Great Plague of London of 1665, and the more recent coronavirus pandemic. There are occasions for eyerolls, anger, laugher, and contempt herein. It seems that although we know history, we are condemned to repeat it anyway.

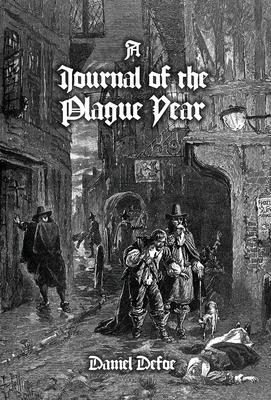

A Journal of the Plague Year: Being Observations or Memorials, Of the Most Remarkable Occurrences, as Well Public as Private, Which Happened in Lond

In November 1664, rumours began winding their way through crowded, filthy, stinking alleyways about the death of two Frenchmen from the Plague at Long Acre. The plague had raged in Amsterdam with incredible violence the year before, as some still remembered, and it appeared to have its made to London by boat. At first, the family with whom the Frenchmen were staying, and then those who had caught the invisible contagion, attempted to conceal it, but soon enough the deaths began to mount, and the cat was out of the bag. Along with the disgusting buboes, the dead carts, and the secret mass graves, people's fervid imagination snowballed too, conjuring all manner of horrors-about the symptoms, about the disease, about pestilential houses filled with rotting corpses-sweeping the city with a foul wave of paranoia and terror. Who had it? Was it in the air? Was it divine punishment? Whither could one flee? Defoe, who lived through these events during infancy, and apparently basing his narrative on his uncle's diary, plus a variety documents, tells the story in the manner of a witness account. Its frightening immediacy makes it far superior, and vastly more engrossing, than Hodges' formal, medically-focused volume on the same subject. In the end, the plague claimed over 68,000 lives, about a quarter of the city's population. Sociologically and in terms of the official response, astonishing, sometimes tragicomical parallels, emerge in the mind of the modern reader, between what became known as the Great Plague of London of 1665, and the more recent coronavirus pandemic. There are occasions for eyerolls, anger, laugher, and contempt herein. It seems that although we know history, we are condemned to repeat it anyway.