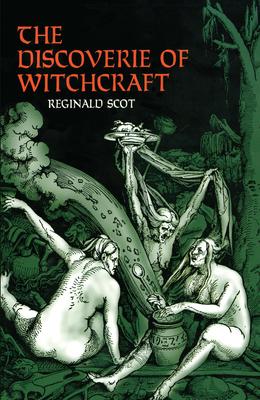

In 1584, when there were few who would even defend witches against these charges, Reginald Scot went one step further. He actually set out to prove that witches did not and could not exist! King James later found Scot's opinion so heretical that he ordered all copies of his book to be burned. But so rich and full of data on the charges against witches, on witch trials and on the actual practice of the black arts was Scot's Discoverie of Witchcraft that it remained a much-used source throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and is still one of the few primary sources for the study of witchcraft today.

At the heart of Scot's book are stories and charges pulled from the writers of the Inquisition about the supposed nature of witches. Scot believed that the utter absurdity of the facts would be enough to stop belief in witchcraft forever. But he also goes on to give opinions of medical authorities, interviews with those convicted of witchcraft, and details about the two-faced practices of those in charge of the inquisitions to show even further why the charges of witchcraft were simply not true. In later chapters Scot details the other side of the question through a study of the black arts that are not purely imaginary. He discusses poisoners, jugglers, conjurers, charmers, soothsayers, figure-casters, dreamers, alchemists, and astrologers and, in turn, sets down the actual practices of each group and shows how the acts depend not upon the devil but upon either trickery or skill. In the process, many of the magician's secrets and much other folk and professional lore of the time is made available to the reader of today.

Shortly after the Spanish Inquisition, directly in the wake of Sprenger and Kramer's Malleus Maleficarum, during the great upsurge of witch trials in Britain, Scot was a direct witness to the witchmonger in one of witch-hunting's bloodiest eras. Whatever your interest in witchcraft -- either historical, psychological, or sympathetic -- Scot, in his disproof, tells you much more about the subject than the many, many contemporary writers on the other side of the question.

In 1584, when there were few who would even defend witches against these charges, Reginald Scot went one step further. He actually set out to prove that witches did not and could not exist! King James later found Scot's opinion so heretical that he ordered all copies of his book to be burned. But so rich and full of data on the charges against witches, on witch trials and on the actual practice of the black arts was Scot's Discoverie of Witchcraft that it remained a much-used source throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and is still one of the few primary sources for the study of witchcraft today.

At the heart of Scot's book are stories and charges pulled from the writers of the Inquisition about the supposed nature of witches. Scot believed that the utter absurdity of the facts would be enough to stop belief in witchcraft forever. But he also goes on to give opinions of medical authorities, interviews with those convicted of witchcraft, and details about the two-faced practices of those in charge of the inquisitions to show even further why the charges of witchcraft were simply not true. In later chapters Scot details the other side of the question through a study of the black arts that are not purely imaginary. He discusses poisoners, jugglers, conjurers, charmers, soothsayers, figure-casters, dreamers, alchemists, and astrologers and, in turn, sets down the actual practices of each group and shows how the acts depend not upon the devil but upon either trickery or skill. In the process, many of the magician's secrets and much other folk and professional lore of the time is made available to the reader of today.

Shortly after the Spanish Inquisition, directly in the wake of Sprenger and Kramer's Malleus Maleficarum, during the great upsurge of witch trials in Britain, Scot was a direct witness to the witchmonger in one of witch-hunting's bloodiest eras. Whatever your interest in witchcraft -- either historical, psychological, or sympathetic -- Scot, in his disproof, tells you much more about the subject than the many, many contemporary writers on the other side of the question.

Paperback

$24.95