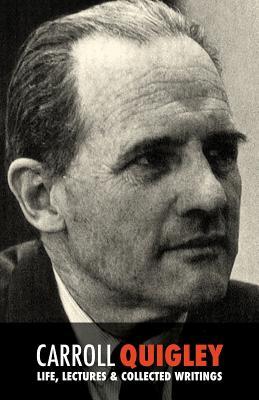

Professor Carroll Quigley was a top American historian and theorist on the evolution of civilizations. He believed that knowledge cannot be divided into parts, that the world can be viewed only as an interlocking, complex system. This view complemented his life: he had reveled in the traditions and contrasts of his neighborhood, eschewed fame in favor of keeping his emotional and social development on track.

In an age characterized by violence, extraordinary personal alienation, and the disintegration of moral values, Quigley chose a life dedicated to rationality. He wanted an explanation that in its very categorization would give meaning to a history which was a record of constant change. Therefore the analysis had to include but not be limited to categories of subject areas of human activity. It had to describe change in categories expressed sequentially in time. It was a most ambitious effort to make history rationally understandable.

On such views, in 1961 Quigley published "The Evolution of Civilizations". Its scope was wide-ranging, covering the whole of man's activities throughout time. It attempted a categorization of man's activities in sequential fashion so as to provide a causal explanation of the stages of civilization.

In 1966, Quigley published "Tragedy and Hope", a work of exceptional scholarship depicting the history of the world between 1895 and 1965. It was a commanding work, 20 years in the writing, that added to Quigley's considerable national reputation as a historian. The book reflected Quigley's feeling that "Western civilization is going down the drain." That was the tragedy. When the book came out in 1966, Quigley thought the whole show could he salvaged; that was his hope.

In the last 12 years of his life, from 1965 to 1977, Quigley taught, observed the American scene, and reflected on his basic values in life. He was simultaneously pessimistic and radically optimistic. Teaching was the core of his professional life and neither his craving to write nor his discouragement with student reaction of the early seventies diminished his commitment to the classroom.

Unlike his underlying faith in the efficacy of teaching, Quigley found little basis for optimism about the future of American society: "We are living in a very dangerous age in which insatiably greedy men are prepared to sacrifice anybody's health and tranquility to satisfy their own insatiable greed for money and power."

Much of the joy of teaching left Quigley in his last years. He complained bitterly that his 1970s college students were woefully under-educated and ill-prepared for college level work and that too many of them had their minds elsewhere, fixated more on bringing about a social revolution than on achieving an education.

Yet pessimism about American society did not weaken a radical optimism rooted in his essential values: nature, people, and God: "The need for others is present on all levels; the physical, emotional, and intellectual. Indeed, every relationship has in it all three aspects. The desire to help others experience these things and to grow as a result of such experiences is called love. Such love is the real motivating force of the universe and is, in its ultimate nature, a manifestation of the love of God. Because while God is pure Reason and man's ultimate goal is Reason, it cannot be reached directly and must always be approached step by step, not alone but in companionship with others, and thus through love. Thus love of others, ultimately love of God, are the steps by which man develops reason and slowly approaches pure Reason."

In the fields of economics we have great recognition for names likes Keynes or Friedman. Professor Quigley, though a top American historian, has escaped our attention. This book, which is a compilation of some of Quigley's writings and most important lectures, is an attempt to fill the void.

One Volume, 400 Page