Born in Berlin in 1769, the young Alexander von Humboldt moved in the circles of Romantic writers and thinkers, studied mining, and worked as an inspector of mines before his "longing for wide and unknown things" made him resign and begin his great scientific expedition. For five years, from 1799 to 1804, Humboldt traveled through Central and South America. He and his collaborator, the French botanist Aim Bonpland, journeyed on foot, by boat, and with mules through grasslands and forests, on rivers and across mountain ranges, and when Humboldt returned to Europe his coffers were full of scientific treasures. His legacy includes a sprawling body of knowledge, from the charge found in electric eels to the distribution of plants across different climate zones, and from the bioluminescence of jellyfish to the composition of falling stars.

But the achievements for which Humboldt was most celebrated in his lifetime fell short of perfection. When he climbed the Chimborazo in Ecuador, then believed to be the highest mountain in the world, he did not quite reach the top; he established the existence of the Casiquiare, a natural canal between the vast water systems of the Orinoco and the Amazon, but this had been known to local people; and his magisterial work, Cosmos, was left unfinished. All of this was no coincidence. Humboldt's pursuit of an all-encompassing, immersive approach to science was a way of finding limits: of nature and of the scientist's own self.

What Humboldt handed down to us is a radically new vision of science: one that has its roots in Romanticism. Seeking the hidden connections of things, he put his finger on the spot where nature and human art correspond. In his understanding, nature is not just an object, separate from us, to be prodded and measured, but something to which we have a deep, sensual affinity, and where the human mind must turn if it wants to truly come to understand itself.

Humboldt achieved this ambition--he was transformed by his experience of nature. He returned to Europe at peace with the person he was, and came to live in Paris for twenty years, then in Berlin, until his death in 1859--the year Darwin published On the Origin of Species.

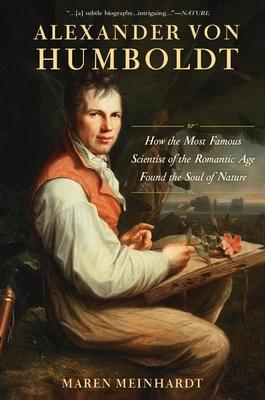

In this concise, illuminating biography, Maren Meinhardt beautifully portrays an exceptional life lived in no less exceptional times. Drawing extensively on Humboldt's letters and published works, she persuasively tells the story of how he became the most admired scientist of the Romantic Age.